“For that which is to count as ‘truth’ from this point onwards now becomes fixed, i.e. a way of designating things is invented which has the same validity and force everywhere, and the legislation of language also produces the first laws of truth, for the contrast between truth and lying comes into existence here for the first time: the liar uses the valid tokens of designation—words—to make the unreal appear to be real…He misuses the established conventions by arbitrarily switching or even inverting the names for things. If he does this in a manner that is selfish and otherwise harmful, society will no longer trust him and exclude him from its ranks. Human beings do not so much flee from being tricked as from being harmed by being tricked” (876).

I find the above quotation from Nietzsche to be of interest. From my understanding of the reading, Nietzsche claims there to be no actual truth, but only a system of concepts constructed by humans in their relationship to the world. If a person is lying, he or she is being untruthful in a manner that is selfish or in a manner that results in harm for society. This description of a liar is important because even the person “telling the truth,” according to Nietzsche, is being untruthful. The liar thus becomes someone who deceives in a manner that results in harm. Given the recent politics in the United States, I thought it would be fun to write a short, and perhaps badly written, story illustrating the construct of the concept of “freedom” and its relationship to untruth, including one that is harmful to society.

Once upon a time there was a Canadian citizen with the unfortunate name of Naseem Osama, and with the unfortunate history of having once worked in the Syrian Intelligence Service prior to his immigration to Canada. Being a benevolent man with a strong sense of family, Osama flew back to Syria one autumn to meet his parents and give them much needed emotional and financial support, as their once prosperous sheep-sheering business was under extreme hardship given the new Syrian leader’s aversion to wool, and the subsequent passing of anti-wool legislation. On a return flight, at a brief layover in New York City, United States Government authorities matched Osama’s name with one on a terrorist watch list, and Osama was formally detained.

“Why are you doing this?” Osama asked the government official. “I demand you free me at once.”

“We are fighting terrorism so as to spread freedom and liberty to all nations of the world,” the government official replied. “Even those living in the backward nations of the Middle East.”

“Oh,” Osama said. “Spreading freedom and liberty. Okay then, go for it. Can I call my wife at least, so she’ll know I won’t be home in time for supper?”

“We can’t do that,” the government official replied. “It is noted on our list that you are a terrorist.”

“In that case,” Osama replied, “I will do whatever is necessary. But I must warn you, my wife gets pretty upset if I don’t call home to tell her I’ll be late.”

During the detention, government officials demanded to know vital terrorist information that one with prior work experience in the Syrian Intelligence Agency would know. Complying with the government officials, Osama informed them that he was now a Canadian citizen and had, in fact, not worked in Syria in over twenty years. When confronted with the question as to the reason of his trip, Osama informed officials of the plight of the wool farmer of Syria, and that his trip had been one to help his sheep-sheering parents cope with such hardship. Government officials, however, noting the fact that Naseem Osama’s name was on their watch list, boarded Osama on a plane and flew him to the obscure, former-soviet republic of Kermackistan for further questioning. Once in Kermackistan, Osama was stripped naked, gagged with a cotton cloth, turned upside down, and doused with water. After several minutes of this, government officials ungagged Osama, and continued questioning.

“We need the information,” one official said.

“I told you all I know,” Osama said, “and I thought Americans weren’t allowed to torture.

“According to law, this isn’t torture,” the official said. “And we didn’t gag you. That was done by the Kermackistanis.”

“Oh,” Osama said. “I guess it’s okay then. But what is the purpose of all this? I want to be freed as soon as possible so that I can see my wife and eat her delicious tuna fish casserole. I’m sure it’s gotten quite cold by now.”

“We are spreading freedom and democracy around the world,” the official said, “so that even those unfortunate souls from the tyrannical lands of the Middle East can be free.”

“Oh,” Osama replied, scratching his head. “In that case, I don’t want to be free. Can I go home now?”

Studying both English literature and film in my undergraduate days, I’ve often pondered about the similarities between the two art forms (especially with the “film is a language” analogy, which does not quite hold up). In early film theory, prior to the age of sound, Hugo Munsterberg had an approach similar to Poulet’s in the psychological study of the act of film spectatorship. According to Munsterberg, film is the optical illusion of a series of photographs projected in a rapid succession that requires the mind of the spectator to create movement. Munsterberg writes: “We [the spectator] do not see objective reality, but a product of our own mind which binds the pictures together” (Munsterberg 402). Furthermore, Munsterberg claims that film spectatorship recreates the mental processes of memory (“bringing up pictures of the past”) and imagination (the overcoming of reality with “fancies and dreams”). Therefore, Munsterberg, like Poulet, sees the art of film occurring in the mind of the person engaging the text. These are wonderful concepts to think about when reading a book or watching a film. They sure as hell give me a great feeling of importance.

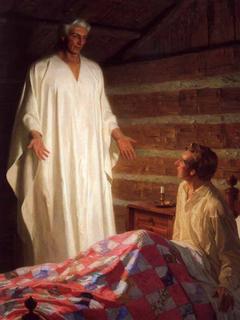

Studying both English literature and film in my undergraduate days, I’ve often pondered about the similarities between the two art forms (especially with the “film is a language” analogy, which does not quite hold up). In early film theory, prior to the age of sound, Hugo Munsterberg had an approach similar to Poulet’s in the psychological study of the act of film spectatorship. According to Munsterberg, film is the optical illusion of a series of photographs projected in a rapid succession that requires the mind of the spectator to create movement. Munsterberg writes: “We [the spectator] do not see objective reality, but a product of our own mind which binds the pictures together” (Munsterberg 402). Furthermore, Munsterberg claims that film spectatorship recreates the mental processes of memory (“bringing up pictures of the past”) and imagination (the overcoming of reality with “fancies and dreams”). Therefore, Munsterberg, like Poulet, sees the art of film occurring in the mind of the person engaging the text. These are wonderful concepts to think about when reading a book or watching a film. They sure as hell give me a great feeling of importance. “He [the Angel Moroni] said there was a book deposited, written upon gold plates, giving an account of the former inhabitants of this continent, and the source from which they sprang. He also said that the fullness of the everlasting Gospel was contained in it, as delivered by the Savior to the ancient inhabitants.” -Joseph Smith describing the visit of an angel, leading to his “unearthing” of what will become the Book of Mormon, 1830.

“He [the Angel Moroni] said there was a book deposited, written upon gold plates, giving an account of the former inhabitants of this continent, and the source from which they sprang. He also said that the fullness of the everlasting Gospel was contained in it, as delivered by the Savior to the ancient inhabitants.” -Joseph Smith describing the visit of an angel, leading to his “unearthing” of what will become the Book of Mormon, 1830.